Bank of Mum and Dad, be warned if your kids haven’t bought a home by 30

Renters who don’t manage to buy a home by their early 30s are less likely to achieve home ownership later in life compared with their parents’ generation, new research has found.

And for every $100,000 that house prices rise, households are up to 3 per cent less likely to be able to get onto the property ladder.

As young people spend more years in higher education and delay starting families compared with previous generations, the rate of home ownership among young people has also fallen.

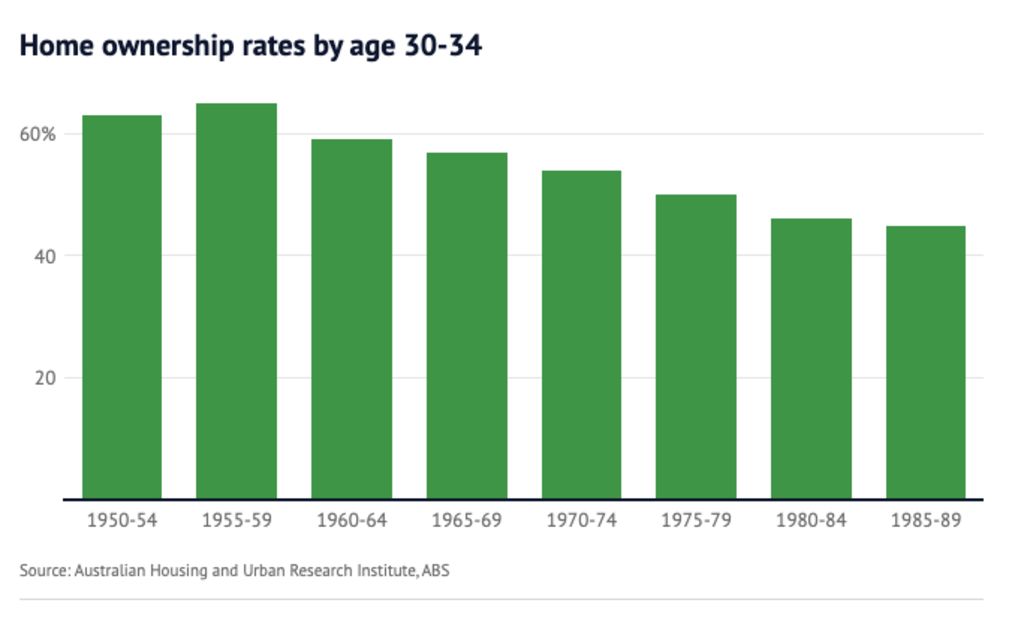

Among household heads born between 1950 and 1954, 63 per cent had bought their first home by the age bracket of 30 to 34, the report by University of Sydney researchers from the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute found.

Thirty-five years later, only 45 per cent of households heads born between 1985 and 1989 had bought a home by their early 30s.

The researchers looked at cohorts who had already reached their early 50s to see if those who had been renting in their 30s had managed to catch up to previous generations in their rates of first home purchase.

Some did, but not all, and 25 per cent of the overall gap remained after 20 years, the research found.

“For a proportion of individuals, it looks like they’re never going to get into home ownership. It’s not simply a case of delaying it,” University of Sydney professor of economics Stephen Whelan, the lead researcher, said.

“What is likely to happen if that gap persists is you’ll have a larger set of individuals moving into retirement who are not home owners.”

This would put additional stresses on households as renters had less security of tenure, and higher living costs in retirement, compared to those retirees who paid off their home. It also puts additional demands on the age pension and Commonwealth Rent Assistance, he said.

As for households aged in their 30s now, Whelan said they would most likely find it harder to achieve home ownership than previous generations as there was no evidence of the trend reversing.

For every $100,000 increase in house prices, the probability of owning a house fell by 2.5 to 3 per cent, the report, Transitions into Home Ownership: A Quantitative Assessment, found.

“In general, if prices go up, you buy less of whatever it is, and housing’s no different,” Whelan said.

“You can make adjustments, you might be able to buy a smaller house, you might be able to buy something a bit further away from the city centre, but on average as these prices increase, the likelihood that individuals purchase a home, for various reasons, decreases.”

The research also revealed the difference help from the “bank of Mum and Dad” could make.

A large gift of $10,000 or more could increase the likelihood of a first home purchase by about 90 per cent, and each extra year of living with parents instead of renting increased the odds by about 30 to 40 per cent.

“Older generations – parents and grandparents – have accumulated large amounts of wealth over the course of their life, and increasingly they’re transferring that wealth through gifts or bequests to younger generations,” Whelan said.

“It makes that transition into home ownership much more likely.”

Whelan noted that, while government assistance schemes had looked to ease the challenge of saving for a home deposit, they were more of a hindrance than a help, as additional funds or savings from grants and stamp duty concessions often increased what first home buyers spent on a property.

Instead, he backed a shift from stamp duty to a broad-based land tax as a way of helping first home buyers.